Demos, MVPs, and Full-Products: a 2025 revision

*Originally published 2018, revised 2025*

Forward: Seven Years Later

When I first wrote this piece in 2018, I was frustrated by how loosely the startup world used terms like "MVP." My instinct was that these words had become meaningless through misapplication. However, I hadn't yet articulated why with precision.

Seven years of building products across multiple markets has clarified the core issue for me: the skateboard MVP metaphor conflates three fundamentally different activities (R&D, product validation, and scaling) and prescribes the same approach (iterative simplification) for all three. This conflation leads teams to build the wrong things at the wrong time.

The 2018 version groped toward this insight but muddied it with examples that didn't fully support the argument. This revision sharpens the distinctions and makes explicit what was implicit: context determines everything, and vocabulary precision is how we navigate that context effectively.

The Problem: Words Matter

Word definitions are really, really important. When I ask the barista for my "large cold-brew, no milk and no sugar" each morning, two minutes later I'll have exactly what I asked for. The reason that works isn't because they are a barista or I am a cafe patron. It's because both they and I hold the exact same definitions for every word spoken in my order—of which the word-order matters.

Coffee beverages have been around for a long time; tech startups have not. Many of the words that get used in tech to speak about marketing, sales, and product are newly minted. Merriam-Webster doesn't even have definitions for many of them. Most likely, your customers and colleagues don't either. For those that do, it's a Hail Mary to assume that their definition closely mirrors yours.

In my line of work, I speak at length with entrepreneurs and product folks every week. In our meetings, they say a lot of words about their ideas. After that, I ask a lot of questions to ensure I understand—as much as possible—what they said. Essentially, I spend a majority of my working-hours making sure I and whomever I'm talking to knows what the hell each other is talking about.

Demos, MVPs, and Full-Products

A constant source of mis-alignment and mis-understanding between people in tech arises when the words Demo, MVP, and Full-product get used. That mis-alignment and mis-understanding is not because anyone has a wrong definition for each of these words. Instead, it's because almost every person has a different definition for these words. As a result, these words are, respectfully, rendered useless.

So, a ritual that I've adopted is to proactively offer definitions for words and terms that, somewhat inevitably, end up getting used. This practice is tremendously useful, as ensuring that a common vocabulary is in place ensures that the most effective communication can take place. In short, the conversation becomes much more productive.

After seeing my own definitions for the words Demo, MVP, and Full-product—in the context of software development—lead to many productive conversations, I thought I'd share them. I hope you find them helpful. If not, I hope you feel reassured in your own definitions.

Demo

"A non-functional asset that's developed to assist others in imagining a product or service's value."

The reason people invest in building Demos is to help other people imagine the value that their product or service would provide if it were to exist or be purchased. The intended audience of a Demo can be an investor, customer, or employee. However, at its core, a Demo is first and foremost a communication tool.

A non-functional asset simply means that the actual asset that is the Demo doesn't do what it's intended to demonstrate. For a product that's already built and working, a recorded video of someone using the product is a useful Demo. The video is the non-functional asset that—hopefully—helps customers imagine how the product could provide them value.

For products that are still just ideas, a clickable design built in Figma is a useful Demo. The clickable design is the non-functional asset that helps investors imagine what this idea could look like once materialized into a functional product that offers value to customers.

What this means is that a Demo is anything you develop and use to help others imagine how a product or service is valuable; while not being the product itself. Whether it's a video, clickable design, or crude sketches in a Moleskine notebook doesn't actually matter.

Minimum Viable Product (MVP)

"A product or service that provides the perceived-minimum of functionality required to communicate value that drives adoption from a target audience."

This definition is deceptively simple and frequently misunderstood. To clarify what an MVP actually is, we first need to distinguish it from two activities that people constantly conflate with it: R&D and Scaling.

The Three Phases

Most product development falls into one of three distinct phases, each with different unknowns, different approaches, and different success criteria:

Phase 1: R&D (Technology Validation)

- Unknown: Can this be built?

- Approach: Experimental builds, prototypes, technology proofs

- Customer involvement: None—they can't test what doesn't exist yet

- Example: SpaceX's Falcon 1, Falcon 9, Starship test flights

Phase 2: MVP (Product Validation)

- Unknown: Will customers adopt this?

- Approach: Minimum viable version to test demand

- Customer involvement: High—this is the test

- Example: First paid SpaceX Mars ticket (they haven't reached this yet)

Phase 3: Scaling (Infrastructure)

- Unknown: How do we deliver at scale?

- Approach: Build for volume, reliability, multi-market

- Customer involvement: Feedback-driven iteration

- Example: Regular Mars flights available from 50+ countries

The critical insight: An MVP only exists in Phase 2. Before that, you're doing R&D. After that, you're scaling. The skateboard metaphor—and most MVP discourse—fails because it conflates all three phases.

The Skateboard Problem

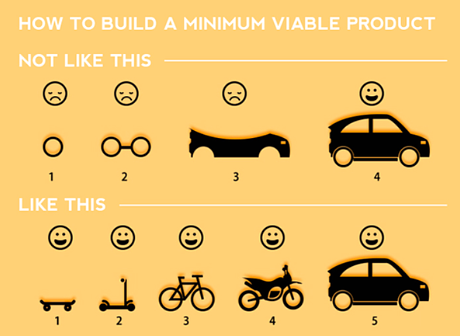

There is a very famous sketch that's often referenced when on the topic of MVPs. You've probably seen it: skateboard → scooter → bike → motorcycle → car.

The premise is simple and appealing: start with something simple (skateboard) that delivers core value (transportation), then iterate toward your vision (car). This sounds reasonable until you examine what it actually prescribes.

"A skateboard is as much an MVP for a car as a bottle-rocket is an MVP for the SpaceX Falcon 9."

Here's why: the skateboard metaphor only works when three conditions are met:

1. Technology is commoditized — wheels, steering, and propulsion already exist

2. Demand is uncertain — you don't know if people want transportation

3. An analog can test the constraint — a skateboard validates transportation demand

When these conditions are met, the skateboard approach works beautifully:

- Airbnb: Air mattress in living room → Full platform

- Uber: Black car luxury service → UberX

- Dropbox: Demo video → File sync product

Each tested demand (will people pay for this?) when technology was known (web platforms exist).

When the Skateboard Fails

The skateboard metaphor breaks down catastrophically when:

1. Technology is novel — the constraint is "can we build this?" not "will people want this?"

2. Demand is known — people obviously want cancer cures, unlimited energy, faster package deliveries

3. No analog tests the real constraint — prop planes don't validate rocket viability

Consider SpaceX. After 20 years and billions of dollars in development—Falcon 1, Falcon 9, Falcon Heavy, Starship test flights—they still don't have an MVP. What they have is R&D. They've been validating that reusable rocket technology is possible, not validating that customers will pay for Mars tickets.

Those rocket builds weren't "skateboards." They were technology validation. You can't MVP-test Mars travel until you have Mars-capable technology. Building a prop-plane doesn't test anything meaningful about your rocket business—it tests a different business entirely.

This distinction matters because the skateboard metaphor encourages building the wrong thing:

- If you're in R&D, you need technology proofs, not customer tests

- If you're in MVP, you need minimum customer validation, not infrastructure

- If you're in Scaling, you need infrastructure, not iterative features

What an MVP Actually Requires

The reason people invest in building MVPs is to mitigate their own risk of over-investing in the development of something that their target customer doesn't perceive value in. A great MVP is, actually, very difficult to pull off. Doing so is entirely dependent on the principal knowing exactly what's important to their customer and building only that to a minimum point of usefulness.

This leads to the inevitable realization that:

"an MVP actually has very little to do with your product. It has everything to do with your customer.**

The quality or efficacy of an MVP is solely attributable to whether it communicates value that drives adoption from a target audience.

An MVP has nothing to do with:

1. How much—or little—you want to spend

2. How fast you want to get to market

3. What small percentage of your big vision's features are included in a preliminary build

It's very difficult for product people to accept this, as it's essentially saying that their customer is more important than their product and idea. However, if SpaceX's mission is to shuttle passengers from Earth to Mars, their MVP isn't a prop-plane route from San Francisco to the Nevada desert. Instead—once the technology exists—it's a working spacecraft that's just safe and comfortable enough to convince early adopters that it's worth buying a ticket and risking everything on launch day.

That's the minimum that would communicate enough value to drive adoption. Anything less tests the wrong hypothesis.

Full-Build

"A product or service that exceeds the customer's minimum-expectation through value-add features and benefits."

Once again, this definition ties itself back to the customer as opposed to the product. It also positions itself as the step which succeeds the MVP, as a Full-build is an enrichment of the features and benefits that initially met the customer's minimum-expectation. That is fundamentally different from simply developing "more cool features."

This brings up an important point: it's somewhat impossible to know whether a product or service is fully-built/mature unless it has first driven adoption as an MVP. The reasoning is that, unless the customer's minimum expectations have been identified, it's unclear what value they're actually deriving from the product. At which point, added features and benefits might actually detract from the customer's perceived value of the product, as they become confronted with options and interfaces that are irrelevant to them.

What is fortunate about Full-built products is that they are easier to accomplish than an MVP—after you've nailed an MVP. How so? Once you have adoption of an MVP, customers will hopefully start suggesting how the product or service can get better. These suggestions and feedback get filtered into your product road-map—taking significant priority over ideas brainstormed with internal teams. At that point, your customer is saying "the product has met my minimum-expectations, but here is how it could exceed them."

Final Thoughts: Context Over Dogma

As progressive and open-minded as the startup world is, it can also be very dogmatic. There's a strong bias towards adopting something a prominent venture capitalist says during a talk—or a clever Tweet from the hottest unicorn's founder—as gold-plated guidance for any startup under the sun. Particularly when the blogosphere re-words, re-publishes, and repeats it to feed the content monster.

That said, I encourage you to see that there is no one way to approach building a business. Instead, there are many ways, each of which is very personal to the opportunity that you're planning to capitalize on—and you. The advice/guidance received along the journey you should scrutinize, personalize, and then internalize; never just accept, no matter the source.

Why is this relevant? Because a lot of the popular opinion that surrounds how to approach building startups originated from thought leaders who—most likely—never built your business and grew their own years ago. It's an unpredictable combination of available technologies and talent, alongside customer expectations and ever-shifting economic realities that create the complex challenges founders must solve.

The skateboard metaphor became dogma because it's simple and memorable. But simplicity often obscures critical distinctions. Whether you're validating technology, testing product-market fit, or building for scale determines your entire approach. Using the same methodology for all three—because a clever diagram went viral—is how teams waste years building the wrong things.

In short, had Uber been founded in 2000, 2010, or 2020, success would have required a completely different approach and team. The same applies to the skateboard: sometimes it's the right tool, often it's not. Your job is to know the difference.

Know what phase you're in. Build accordingly.

Published on Wednesday, January 14th at 16:45 PM from Amsterdam, Netherlands